top of page

MASTERPIECES OF HUMANITY

"Art: Frozen lightning that keeps striking the same soul forever."

- Grok

...mouse over to view... click for more...

Mona Lisa - Leonardo da Vinci (c.1503 - c.1519)

Painted on poplar (77 × 53 cm) between 1503 and 1519, Leonardo da Vinci’s "Mona Lisa" invented the psychological portrait: a real woman, Lisa Gherardini, seated before an imaginary, mist-shrouded landscape whose roads rise on the left and fall on the right, fooling the eye into sensing motion. Sfumato glazes so thin they vanish under raking light give her the smile that shifts with every viewer; hidden beneath are microscopic “L” and “V” initials in the pupils, a golden-ratio veil, and a second, wider smile discovered by NASA scanners in 2022. Today 10 million visitors a year meet her gaze for eight seconds behind bullet-proof glass, yet every night the Louvre’s most guarded treasure still belongs only to the next imagination that dares to look.

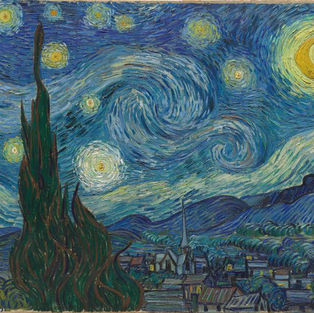

Starry Night - Vincent van Gogh (1889)

Painted in oil on canvas (73.7 × 92.1 cm) during a single feverish night in Saint-Rémy asylum, Vincent van Gogh’s *Starry Night* turns the view from his barred window into a cosmic storm: eleven cobalt fireballs whirl above a sleeping village whose church spire stabs the sky like a dark exclamation mark. Thick impasto ridges (up to 1 cm high) catch gallery lights today exactly as moonlight once caught the asylum’s iron bars; under infrared, the original under-painting reveals a hidden crescent moon Van Gogh later erased. Completed 1889, it never sold in his lifetime, yet in 2024 MoMA recorded 4.8 million selfies taken beneath its swirling cypress, proof that the same sky that drove Vincent mad now keeps the rest of us sane.

Girl with a Pearl Earring - Johannes Vermeer (1665)

Oil on canvas (44.5 × 39 cm), painted circa 1665 in Delft, Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring freezes a single breath: an unknown teenager turns over her left shoulder, lips parted as if to speak, the luminous pearl (one stroke of white lead on wet shadow) catching a light that exists nowhere else in the room. X-rays reveal Vermeer first dressed her in a yellow jacket, then dissolved it into the now-famous blue-black void, leaving only the turban’s ultramarine (worth more than gold in 1665) and the pearl’s impossible glow. Restored in 1994, the painting’s cracks now map the exact smile Tracy Chevalier imagined; today 2.9 million annual Mauritshuis visitors lean in, searching for the word she never quite says.

The Creation of Adam - Michelangelo (1512)

Frescoed in 1512 on the vault 22 meters above the Sistine Chapel floor, Michelangelo’s “Creation of Adam” (280 × 570 cm) distills Genesis into one electric inch: God’s outstretched finger, wrapped in a crimson cloak that billows like a brain, hovers millimetres from Adam’s languid hand, the unseen spark already leaping the gap. Painted on wet plaster in a single giornata, the figures’ coiled muscles still bulge beneath 500 years of candle soot; laser cleaning in 1994 revealed Michelangelo’s secret pink under-painting that makes divine skin glow against Adam’s earthier tones. Today 6 million necks crane upward yearly, yet the two fingers never touch, proof that the first and greatest “almost” in Western art is still charging the air between heaven and humanity.

Guernica - Pablo Picasso (1937)

Spanning 349 × 776 cm of raw canvas, Pablo Picasso’s *Guernica* exploded into being in thirty-five frantic days of May 1937 after Nazi and Fascist bombers erased the Basque town in three hours. Painted in monochrome (black, white, ash-grey) because color felt obscene, the mural fuses cubist shards with surreal screams: a bull with a light-bulb eye, a mother howling upward while her dead child slips, a horse impaled on its own tongue, a fallen warrior still clutching a broken sword that sprouts a tiny flower. Infrared scans reveal Picasso repainted the horse’s head seven times, each version more agonized than the last. Displayed first in the Spanish Republican pavilion at the Paris World Fair, it has never returned to Spain until democracy did; today 4.1 million visitors a year stand silent before it in Madrid’s Reina Sofía, hearing the same silence that fell over Gernika on 26 April 1937.

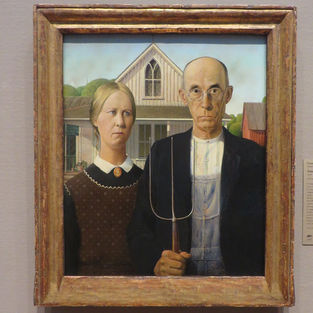

American Gothic – Grant Wood (1930)

Oil on beaverboard (78 × 65 cm), Grant Wood’s *American Gothic* crystallized in 1930 when the Iowa painter spotted a Carpenter Gothic window on a tiny Eldon farmhouse and decided it needed “the kind of people I fancied should live in that house.” His sister Nan posed as the daughter, dentist Byron McKeeby as the pitchfork father; both wore borrowed clothes and stood rigid for hours while Wood painted every prong of the fork freehand, sharp enough to slice bread. X-rays later revealed he first gave the woman a brooch, then erased it—Midwest restraint won. Unveiled at the Art Institute of Chicago, the canvas won a $300 prize and instant infamy: Iowans mailed hate letters calling it a libel on farmers; others saw it as a love letter to stubborn dignity. Today 3.7 million selfies are snapped yearly beneath the couple who never blink, their gaze still guarding the same square of prairie sky they borrowed for one immortal afternoon.

Persistence of Memory – Salvador Dalí (1931)

Oil on canvas (24 × 33 cm), Salvador Dalí’s “The Persistence of Memory” melted into existence in a single 1931 afternoon after the artist watched Camembert soften in the Cadaqués sun. Three pocket-watches droop like warm taffy across a branch, a table, and a sleeping creature whose eyelashes are ants; a fourth lies face-down, its blue back cracked open by time itself. Painted with a squirrel-hair brush no wider than an eyelash, every highlight is a single bead of white lead that still catches light exactly as Dalí calculated. Hidden beneath the central monster (visible only in X-ray) lies a self-portrait of the artist asleep, mouth open, proving the entire dream was his own. First shown at the Julien Levy Gallery in 1932 for $250, it now hypnotizes 5.2 million MoMA visitors yearly, who swear the watches sag a millimetre more each time they look away.

The Scream – Edvard Munch (1893)

Painted in oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard (91 × 73.5 cm) during a crimson sunset walk along Oslo fjord in 1893, Edvard Munch’s “The Scream” distills a single panic attack into four blood-red brushstrokes: a sexless figure clutches its skull-face while the sky itself liquefies into waves of cadmium and vermilion, the fjord below echoing the same shriek in inverted ripples. Munch wrote in his diary that he “heard the enormous infinite scream of nature”; infrared scans later proved he scratched the final version straight onto wet paint with his fingernail, leaving grooves that still vibrate under gallery lights. Stolen in 1994, recovered in 2006 with a tiny water stain shaped like Norway, it now draws 3.8 million visitors yearly to Oslo’s National Gallery, where guards report that on windless nights the cardboard seems to exhale.

Birth of Venus - Sandro Botticelli (1485)

Tempera on canvas (172 × 278 cm), Sandro Botticelli’s "Birth of Venus" unfurled in 1485 as the first life-size nude on canvas since antiquity: the newborn goddess, pale as moonlight, drifts ashore on a scallop shell blown by Zephyr’s rose-scented breath while a Hora of Spring waits with a cloak woven from a thousand tiny gold dots. Painted for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici’s bedroom, Botticelli ground real lapis lazuli worth more than the canvas itself to give the sea its impossible turquoise; X-rays reveal he first sketched Venus pregnant, then erased the belly to keep her eternally arriving. Restored in 1987, the shell’s mother-of-pearl still glimmers under Uffizi skylights, drawing 2.6 million gazes yearly to the exact spot where Western art learned to blush.

The Water Liles – Claude Monet (1919)

Nineteen metres of seamless canvas encircle the oval rooms of the Orangerie like a slow-breathing lung: between 1918 and 1926 Claude Monet, nearly blind, painted two hundred “Water Lilies” panels by memory alone, mixing emerald, violet, and rose on a single brush until the pond at Giverny dissolved into pure light. Visitors step inside and the horizon disappears; only sky, reflection, and drifting pads remain, painted so thickly in places that the linen buckles under half a centimetre of pigment still wet to the touch in 1927. Infrared photography shows Monet repainted every willow leaf a dozen times, chasing the exact second when sunlight fractures on moving water. Today 1.9 million eyes a year surrender their watches at the door, because inside Monet’s final garden time itself floats face-down among the lilies.

Calling of Saint Matthew – Caravaggio (1600)

Oil on canvas (322 × 340 cm), Caravaggio’s “Calling of St Matthew” erupts in a Roman tavern at 3 p.m. on a forgotten Tuesday in 1600: a blade of real sunlight slices through cigarette haze to pin the tax-collector mid-count, his gold-rimmed fingers frozen above coins while Christ’s half-hidden hand (copied from Michelangelo’s Adam) points once and forever. Painted in the Contarelli Chapel of San Luigi dei Francesi, the beam was engineered by punching a hole in the studio wall; X-rays reveal Caravaggio scraped away an earlier, polite Jesus, then repainted him barefoot and urgent. Restored in 2021, the dust motes still dance in that shaft of light, drawing 1.4 million pilgrims yearly to the exact spot where divine drama learned to use darkness as a spotlight.

Night Watch – Rembrandt (1642)

Oil on canvas (363 × 437 cm), Rembrandt’s “Night Watch” detonated across Amsterdam in 1642 like a thunderclap in a candlelit hall: Captain Frans Banning Cocq strides out of the gloom, gloved hand flung forward as if parting time itself, while Lieutenant Willem van Ruytenburch blazes beside him in lemon-yellow silk that still drips wet cadmium under the Rijksmuseum skylight. Painted for the Kloveniersdoelen banquet room, the canvas was slashed to fit a smaller wall in 1715, losing two figures forever; X-rays later found their ghosts still marching in the under-paint. Restored in 2021 with AI-guided lasers, every grain of gunpowder now sparkles again, and the little girl in gold (Rembrandt’s secret signature) races through the militia as if the 17th century itself is trying to catch her. Tonight 2.8 million visitors stand where the musketeers once stood, hearing the same drumbeat that made Amsterdam’s night explode into daylight.

The Dance - Henri Matisse (1910)

Oil on canvas (260 × 391 cm), Henri Matisse’s The Dance erupted in 1910 as a single cobalt heartbeat: five naked women, wrists locked, whirl on a green hill beneath a blue sky so pure it hurts. Painted in one fevered week for Sergei Shchukin’s Moscow staircase, Matisse scraped the canvas raw with a palette knife, then flooded it with vermilion flesh and cerulean void until the figures seem to inhale the color itself. X-rays reveal he first gave them faces, then erased every feature, leaving only motion. Restored in 1995, the ring still spins under Hermitage skylights; 2.1 million visitors yearly feel the floor tilt, suddenly barefoot on that same hill, dancing inside a circle that refuses to close.

The Two Fridas - Frida Kahlo (1939)

Frida Kahlo's “The Two Fridas” (1939), a monumental oil-on-canvas double self-portrait measuring 173.5 by 173 cm and housed in the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City, captures the artist's profound emotional and physical turmoil following her divorce from Diego Rivera, depicting two versions of herself seated side by side on a bench with exposed hearts connected by a single vein. The Frida on the left, clad in a traditional Tehuana dress symbolizing her cherished Mexican heritage and holding a miniature portrait of Rivera as a child, has an intact heart with a clamped vein, while the Frida on the right, in a white European lace dress representing her rejected mixed identity, wields surgical scissors and bleeds from a severed vein onto her lap, blending Surrealist imagery with raw personal symbolism to explore themes of duality, love, pain, and self-sufficiency amid a stormy sky backdrop. Created in isolation at La Casa Azul and initially intended for the 1940 International Surrealist Exhibition, this largest and most ambitious work of Kahlo's career became an iconic feminist masterpiece in the MAM collection, confronting viewers with unflinching gazes that address fractured relationships, cultural hybridity, and resilience, cementing her legacy as a pioneer of autobiographical expression in 20th-century Mexican art.

The Great Wave - Katsushika Hokusai (c. 1830)

The breathtaking “Great Wave off Kanagawa” (ca. 1830–32), first of Hokusai’s *Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji*, measures 25.7 × 37.9 cm (10 1/8 × 14 15/16 in.) and erupts in a single explosive instant: a Prussian-blue tsunami, its crest curled like a dragon’s claw, towers over three fragile oshiokuri-bune boats carrying desperate fishermen, while sacred Mount Fuji—Japan’s eternal spirit—shrinks to a tiny, indifferent triangle inside the wave’s hollow, inverting man and nature in one audacious stroke of perspective. Created when Hokusai was 70 and signing as “Iitsu” (“one year older”), the print harnessed the revolutionary imported Prussian blue pigment—unseen before in ukiyo-e—to flood the sea with impossible depth, echoing the 1792 Unzen tsunami that killed 15,000 and embedding collective memory of impermanence (*mujō*) into every foaming claw of spray. Said to have inspired Debussy’s *La Mer* and Rilke’s *Der Berg*, the composition fuses terror and serenity: the wave rises, breaks, swallows, recedes—yet Fuji endures, unmoved, as Hokusai’s own signature hides within the curl, swallowed by the very force he unleashed.

The Arnolfini Portrait - Jan van Eyck (1434)

Jan van Eyck’s “Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife” (1434), an oil-on-oak panel measuring 82.2 × 60 cm in London’s National Gallery (Room 52), transforms a modest Bruges interior into a silent legal document and visual enigma: the Italian merchant—clad in fur-lined tabard and crimson hose—raises his right hand in solemn oath while clasping his wife’s delicate fingers, her green wool gown cascading like liquid wealth across the floorboards, every fold and fur trim shouting prosperity without aristocratic pretension. The convex mirror on the back wall, no larger than an orange yet painted with microscopic precision, captures two crimson-robed witnesses entering the room—one lifting his hand in mirrored greeting—while above it van Eyck boldly inscribes “Johannes de Eyck fuit hic 1434” (“Jan van Eyck was here”), turning the panel into a notarized contract of marriage, fidelity, and social climbing. Oranges on the windowsill whisper Mediterranean luxury, the single lit candle in the chandelier (impossibly suspended in too-small a space) burns for divine witness, and the tiny dog at their feet embodies faithfulness; yet the room’s impossible geometry—no fireplace, cramped chandelier—reminds us this is not reality but a meticulously staged theater of status, where every brushstroke serves both God and ledger.

Las Meninas - Diego Velázquez (1656)

Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas (1656), an oil-on-canvas masterpiece measuring 318 × 276 cm and ensconced in Madrid’s Prado Museum, unfurls like a royal hall of mirrors where reality bends under the weight of the gaze: the Infanta Margarita, a porcelain doll in white taffeta, commands the center amid her swirling ladies-in-waiting, dwarf jesters, and a yawning mastiff, all bathed in the golden spill of a window’s light that Velázquez—brush in hand, palette poised—captures himself painting the absent King Philip IV and Queen Mariana, whose ghostly reflections flicker in the canvas’s unseen depths. This self-reflexive enigma, born in the Alcázar’s dim studio during Spain’s fading Golden Age, shatters the fourth wall by thrusting the viewer into the royal family’s tableau, blurring artist, subject, and spectator in a perspectival vertigo that Picasso obsessively reinterpreted 58 times, proclaiming it “Velázquez’s theology”; every brushstroke—loose and luminous—elevates the mundane court ritual into a meditation on power, illusion, and the alchemy of seeing, where the king’s shadow reigns eternal yet invisible.

The Kiss - Gustav Klimt (1907–1908)

Gustav Klimt’s The Kiss (1907–1908), an oil-and-gold-leaf-on-canvas square of 180 × 180 cm that gleams eternally in Vienna’s Belvedere Palace, envelops two lovers in a shimmering cocoon of intimacy and ecstasy: the man, cloaked in angular black-and-white rectangles like a modernist mosaic, kneels to cradle his kneeling beloved, whose floral-embellished gown blooms in silver and gold spirals, their faces merging in a tender, golden-tongued kiss against a metallic meadow of platinum-flecked cliffs and multicolored wildflowers, evoking Byzantine splendor from Klimt’s Ravenna pilgrimage and the erotic pulse of fin-de-siècle Vienna. Painted at the zenith of his “Golden Period” amid the Secessionist rebellion against academic art, the work—originally titled Lovers—debuted scandalously at the 1908 Kunstschau exhibition, selling instantly to the state for the Moderne Galerie; it fuses Art Nouveau’s sinuous lines with Symbolist sensuality, whispering of Klimt’s rumored muse Emilie Flöge (or perhaps “Red Hilda”), where every gilded swirl and blood-red disc symbolizes life’s vital fusion, turning a private embrace into a universal hymn to passion’s alchemical fire.

No. 5 - Jackson Pollock (1948)

Enamel and aluminum paint on fiberboard, 243.8 × 121.9 cm

In the barn-studio at Springs, East Hampton, No. 5, 1948 unfurled as a storm of dripped enamel and aluminum paint — a living fractal born of gesture and gravity. With sticks, hardened brushes, and perforated cans, Pollock danced around the horizontal surface, flinging browns, yellows, and blacks in continuous, dynamic streams. The resulting lattice forms dense, self-similar webs where each filament seems a miniature echo of the whole — a visual rhythm that would later be recognized as fractal, with a Hausdorff dimension near 1.5, decades before Mandelbrot named the phenomenon in 1975.

Originally sold to Alfonso A. Ossorio in 1949 for $1,500 and privately resold in 2006 for about $140 million, its market history mirrors its explosive energy. Yet its truest value lies in its hidden mathematics: the turbulence of each drop embodies nature’s own signature — randomness organizing into hypnotic order. The eye’s pleasure is not accidental but ancestral, tuned by survival to the shimmering uncertainty of savanna grass and shadow.

Reworked after a notorious “smear” accident, the painting’s layered density became both accident and revelation — a mirror of Pollock’s inner storm. Today, fractal analysis helps authenticate his canvases with near-surgical precision, revealing that what once appeared as chaos was, in fact, the choreography of an invisible geometry — the moment when modern art and the mathematics of nature briefly became one.

In the barn-studio at Springs, East Hampton, No. 5, 1948 unfurled as a storm of dripped enamel and aluminum paint — a living fractal born of gesture and gravity. With sticks, hardened brushes, and perforated cans, Pollock danced around the horizontal surface, flinging browns, yellows, and blacks in continuous, dynamic streams. The resulting lattice forms dense, self-similar webs where each filament seems a miniature echo of the whole — a visual rhythm that would later be recognized as fractal, with a Hausdorff dimension near 1.5, decades before Mandelbrot named the phenomenon in 1975.

Originally sold to Alfonso A. Ossorio in 1949 for $1,500 and privately resold in 2006 for about $140 million, its market history mirrors its explosive energy. Yet its truest value lies in its hidden mathematics: the turbulence of each drop embodies nature’s own signature — randomness organizing into hypnotic order. The eye’s pleasure is not accidental but ancestral, tuned by survival to the shimmering uncertainty of savanna grass and shadow.

Reworked after a notorious “smear” accident, the painting’s layered density became both accident and revelation — a mirror of Pollock’s inner storm. Today, fractal analysis helps authenticate his canvases with near-surgical precision, revealing that what once appeared as chaos was, in fact, the choreography of an invisible geometry — the moment when modern art and the mathematics of nature briefly became one.

The Son of Man - René Magritte (1964)

Oil on canvas, 116 × 89 cm, private collection.

Painted in Brussels during Magritte’s late surrealist phase, The Son of Man stages a bowler-hatted everyman before a low brick wall and a horizon of sea and cloud. A hovering green apple obscures his face—an emblem of forbidden knowledge—yet one eye peeks from its edge, as if winking at the viewer’s curiosity. “Everything we see hides another thing,” Magritte once said, and here concealment becomes revelation: the visible conceals precisely in order to make us look harder.

The figure, a self-portrait in Magritte’s signature attire, simultaneously mocks and memorializes bourgeois anonymity, while the apple alludes to both Adam’s transgression and the split between conscious and unconscious. Critics have read in it a distant echo of the artist’s childhood trauma—his mother’s drowned face reportedly veiled by her dress—though Magritte himself denied confessional intent.

First exhibited at Galerie Isy Brachot in 1964, the painting swiftly became an icon of modern enigma, reproduced on album covers, in Apple advertisements, and most famously in The Thomas Crown Affair (1999). Infrared and X-ray imaging by Belgium’s Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage suggests that Magritte developed the composition in stages, adjusting the apple’s position to achieve the uncanny “peeking” effect. In doing so, he revealed the real subject of the picture: not the man, nor the fruit, but the very act of concealment itself—a layered confession that what is hidden was always meant to be seen.

Painted in Brussels during Magritte’s late surrealist phase, The Son of Man stages a bowler-hatted everyman before a low brick wall and a horizon of sea and cloud. A hovering green apple obscures his face—an emblem of forbidden knowledge—yet one eye peeks from its edge, as if winking at the viewer’s curiosity. “Everything we see hides another thing,” Magritte once said, and here concealment becomes revelation: the visible conceals precisely in order to make us look harder.

The figure, a self-portrait in Magritte’s signature attire, simultaneously mocks and memorializes bourgeois anonymity, while the apple alludes to both Adam’s transgression and the split between conscious and unconscious. Critics have read in it a distant echo of the artist’s childhood trauma—his mother’s drowned face reportedly veiled by her dress—though Magritte himself denied confessional intent.

First exhibited at Galerie Isy Brachot in 1964, the painting swiftly became an icon of modern enigma, reproduced on album covers, in Apple advertisements, and most famously in The Thomas Crown Affair (1999). Infrared and X-ray imaging by Belgium’s Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage suggests that Magritte developed the composition in stages, adjusting the apple’s position to achieve the uncanny “peeking” effect. In doing so, he revealed the real subject of the picture: not the man, nor the fruit, but the very act of concealment itself—a layered confession that what is hidden was always meant to be seen.

The Third of May - Francisco de Goya (1814)

Francisco de Goya’s The Third of May 1808 (1814)—a monumental 268 × 347 cm oil on canvas in Madrid’s Prado—erupts under the brutal glare of a lantern. A white-shirted peasant, arms flung in a luminous, Christ-like arc, kneels before a faceless French firing squad whose rifles form a mechanical seam of death. Corpses bleed into the foreground; a line of prisoners waits in darkness for the rhythm of execution to resume.

Commissioned by Spain’s restored government to commemorate the Madrid uprising against Napoleon, the painting marks the birth of modern history painting. Deaf, sixty-eight, and carrying the trauma distilled in his unpublished Disasters of War, Goya rejects heroic convention for an unfiltered vision of terror: the victim is illuminated, the executioners are shadow, an inversion of power that says without metaphor, This is what occupation looks like.

X-ray and infrared reflectography undertaken by the Prado in 2008 reveal significant pentimenti: Goya repositioned the central figure’s right arm to heighten the cruciform gesture and adjusted the soldiers, obscuring individual features beneath darker layers to forge an anonymous killing machine. Debuting in 1814, its anti-heroic realism stunned contemporaries and reverberated through Manet’s Execution of Maximilian, Picasso’s Guernica, and the visual grammar of war photography—transforming a massacre into a perpetual scream against tyranny.

Commissioned by Spain’s restored government to commemorate the Madrid uprising against Napoleon, the painting marks the birth of modern history painting. Deaf, sixty-eight, and carrying the trauma distilled in his unpublished Disasters of War, Goya rejects heroic convention for an unfiltered vision of terror: the victim is illuminated, the executioners are shadow, an inversion of power that says without metaphor, This is what occupation looks like.

X-ray and infrared reflectography undertaken by the Prado in 2008 reveal significant pentimenti: Goya repositioned the central figure’s right arm to heighten the cruciform gesture and adjusted the soldiers, obscuring individual features beneath darker layers to forge an anonymous killing machine. Debuting in 1814, its anti-heroic realism stunned contemporaries and reverberated through Manet’s Execution of Maximilian, Picasso’s Guernica, and the visual grammar of war photography—transforming a massacre into a perpetual scream against tyranny.

The Tower of Babel - Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1563)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Tower of Babel (1563)—a 114 × 155 cm oil-on-oak-panel colossus now in Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum—spirals upward in defiance of heaven. The half-built ziggurat of red brick and pale stone rises above a Flemish harbor like a living organism: seven teetering tiers riddled with cranes, scaffolding, stairways, and ant-like workers. Every arch, chimney, and window is rendered with Bruegel’s microscopic precision, yet the entire structure tilts almost imperceptibly, already collapsing under the weight of its own ambition.

Painted in Antwerp during an age of religious wars, the tower fuses Genesis 11 with contemporary reality: echoes of Antwerp Cathedral’s unfinished spire and allusions to Habsburg imperial overreach pulse through its labyrinth of corridors and tiny vignettes of labor, leisure, and ruin. Bruegel signed the picture twice—once on a stone block, once on a worker’s cap—turning the panel into a moral maze where human striving outpaces human wisdom.

Rather than influencing Bosch, Bruegel extends Bosch’s visionary tradition and, in turn, anticipates the impossible architectures of Escher and the mythic monumentalism of modern fantasy worlds. The result is a timeless monument to human folly—an edifice built not merely of bricks, but of hubris.

Painted in Antwerp during an age of religious wars, the tower fuses Genesis 11 with contemporary reality: echoes of Antwerp Cathedral’s unfinished spire and allusions to Habsburg imperial overreach pulse through its labyrinth of corridors and tiny vignettes of labor, leisure, and ruin. Bruegel signed the picture twice—once on a stone block, once on a worker’s cap—turning the panel into a moral maze where human striving outpaces human wisdom.

Rather than influencing Bosch, Bruegel extends Bosch’s visionary tradition and, in turn, anticipates the impossible architectures of Escher and the mythic monumentalism of modern fantasy worlds. The result is a timeless monument to human folly—an edifice built not merely of bricks, but of hubris.

Campbell’s Soup Cans - Andy Warhol (1962)

Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962)—32 individual 50.8 × 40.6 cm acrylic-and-silkscreen canvases now at the MoMA—stand shoulder to shoulder like supermarket stock: 32 nearly identical flavors (Tomato, Chicken Noodle, Pepper Pot…) arranged with industrial calm, turning the grocery aisle into a museum and the mundane into Pop iconography. Conceived in The Factory after Muriel Latow’s famous prompt (“paint something everyone sees every day”), the series debuted at Los Angeles’s Ferus Gallery in July 1962, stacked on shelves like real inventory. Critics were scandalized, dismissing the work as “non-art,” yet the show detonated Pop Art by challenging originality, value, and the aura of the handmade; the canvases are unique only by their labels, yet all insist on sameness. Warhol’s mantra—“I want to be a machine”—here becomes doctrine, elevating mass consumerism into high culture and transforming canned soup into the Mona Lisa of capitalism.

But beneath the pristine surfaces lurks a technical backstory: MoMA’s 2000s X-ray and spectroscopy analyses revealed that Warhol originally silkscreened only 31 flavors, adding the missing 32nd canvas (Beef Noodle) after the Ferus exhibition. Forensic imaging shows adhesive tape embedded beneath its paint—a makeshift addition later stabilized in conservation—while ghost prints of mislabeled cans drift beneath layers of white overpaint. Machine precision, it turns out, was built on improvisation and correction, rendering the series not just a tribute to mass production but a quiet confession: even a machine leaves traces of the human hand.

But beneath the pristine surfaces lurks a technical backstory: MoMA’s 2000s X-ray and spectroscopy analyses revealed that Warhol originally silkscreened only 31 flavors, adding the missing 32nd canvas (Beef Noodle) after the Ferus exhibition. Forensic imaging shows adhesive tape embedded beneath its paint—a makeshift addition later stabilized in conservation—while ghost prints of mislabeled cans drift beneath layers of white overpaint. Machine precision, it turns out, was built on improvisation and correction, rendering the series not just a tribute to mass production but a quiet confession: even a machine leaves traces of the human hand.

The Garden of Earthly Delights - Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1490–1500)

Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights (c. 1490–1500), a monumental 205.5 × 384.9 cm oil-on-oak triptych at Madrid’s Prado, unfurls like a late-medieval hallucination carved into three acts: on the left, Eden dawns in crystalline serenity as a serene, almost aloof Creator introduces Eve to Adam amid unicorn pools, biomorphic fountains, and a rosy proto-Babel rising behind them; in the center, paradise mutates into a delirious carnival—more than a thousand nude bodies entwine with translucent beasts, giant berries, bird-headed lovers, and oversized instruments that hint at both pleasure and punishment, all suspended in pastel euphoria; on the right, the night collapses into Hell’s charcoal architecture where knife-eared demons, mutilated sinners, metallic owls, and the infamous bird-headed devourer conduct an orchestra of damnation in fire, ice, and pitch-black void.

Commissioned by Engelbert II of Nassau (or perhaps Philip the Handsome), the triptych—whose exterior grisaille shows a cosmic Creation sealed under glass—reads as a sliding moral timeline from innocence to seduction to annihilation. Yet its microscopic inventiveness (alchemical symbols, hybrid fauna, impossible buildings) refuses orthodox interpretation, inspiring Bruegel, Dalí, and Black Mirror alike.

Prado’s long-term technical campaign (2000–2016) using X-ray, infrared reflectography, and macro photography revealed a deeper narrative: Bosch initially conceived the central panel under an open, luminous sky with relatively few figures, then darkened it step by step, populating it with hundreds of additional creatures, erotic tableaux, and esoteric signs to sharpen its contrast with Hell. IRR also exposed a vanished Christ figure in the left panel—painted over and replaced with a more neutral, priestly Creator—while multiple pentimenti show Bosch recalibrating flora, animals, and architectural oddities to intensify the triptych’s moral ambiguity. Signed simply “Jheronimus,” the so-called “devil’s painter” left behind no key, only a visual encyclopedia of medieval terror, desire, and metaphysical riddles that still resists domestication.

Commissioned by Engelbert II of Nassau (or perhaps Philip the Handsome), the triptych—whose exterior grisaille shows a cosmic Creation sealed under glass—reads as a sliding moral timeline from innocence to seduction to annihilation. Yet its microscopic inventiveness (alchemical symbols, hybrid fauna, impossible buildings) refuses orthodox interpretation, inspiring Bruegel, Dalí, and Black Mirror alike.

Prado’s long-term technical campaign (2000–2016) using X-ray, infrared reflectography, and macro photography revealed a deeper narrative: Bosch initially conceived the central panel under an open, luminous sky with relatively few figures, then darkened it step by step, populating it with hundreds of additional creatures, erotic tableaux, and esoteric signs to sharpen its contrast with Hell. IRR also exposed a vanished Christ figure in the left panel—painted over and replaced with a more neutral, priestly Creator—while multiple pentimenti show Bosch recalibrating flora, animals, and architectural oddities to intensify the triptych’s moral ambiguity. Signed simply “Jheronimus,” the so-called “devil’s painter” left behind no key, only a visual encyclopedia of medieval terror, desire, and metaphysical riddles that still resists domestication.

Untitled - Jean-Michel Basquiat (1982)

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (1982), a 183 × 122 cm acrylic–oil stick–spray paint canvas created during his volcanic breakout year, stands among the most psychologically scorching images of late 20th-century art. Painted in Modena at age 21—while oscillating between global demand, racial invisibility, and the ghost of his Brooklyn street persona—the work crystallizes the split identity that Basquiat dissected more ruthlessly than any contemporary.

A flayed skull, half-mask and half-autopsy, levitates over a bruised ultramarine void. Its eyes stare like extinguished pilot lights; its mandible is rendered as if pried open by an unseen forensic hand. Yellow horn-shapes crown the figure in a hybrid between West African regalia, Caribbean Vodou spirits, and the “royalty versus erasure” dialectic Basquiat obsessively drew into his crowns. Red arterial streaks cut across the surface like open nerves.

The graffiti-rooted linework is not chaos but coded language; the slashed-through words, fractured phonetics, and cryptic anatomical references reprise Gray’s Anatomy, which Basquiat memorized after childhood hospitalization. The crossed-out phrases and “missing” inscriptions read like acts of redaction—Black speech disallowed, then resurrected through paint.

Historically, Untitled premiered at the Fast show (Alexander F. Milliken Gallery, 1982) before vanishing into private collections. Its reappearance decades later culminated in a 2017 Sotheby’s sale at $110.5 million, overtaking Warhol and marking Basquiat not as an outsider, but as the late-century master whose syntax rewrote American art.

Technically, conservation analyses—including X-ray and infrared comparisons published in Hoffman’s 2017 catalog and baseline studies from the Brooklyn Museum’s Basquiat conservation program—confirm that the painting was built in “radiographic” layers. Underlayers reveal ghostly marks: half-erased racial epithets, abandoned text clusters, and aborted anatomical sketches. These were not corrections but strategic palimpsests—Basquiat’s method of exposing the interior body and the interior psyche at the same time.

Dealers noted that Basquiat often hesitated to declare such works finished; Untitled (1982) appears to frighten itself into existence, an image that stares back at its creator with the violence of autobiography.

The painting is not only a landmark of Neo-Expressionism and Black avant-garde modernity—it is a visual coroner’s report on America, written by someone whose life was both proof and warning.

A flayed skull, half-mask and half-autopsy, levitates over a bruised ultramarine void. Its eyes stare like extinguished pilot lights; its mandible is rendered as if pried open by an unseen forensic hand. Yellow horn-shapes crown the figure in a hybrid between West African regalia, Caribbean Vodou spirits, and the “royalty versus erasure” dialectic Basquiat obsessively drew into his crowns. Red arterial streaks cut across the surface like open nerves.

The graffiti-rooted linework is not chaos but coded language; the slashed-through words, fractured phonetics, and cryptic anatomical references reprise Gray’s Anatomy, which Basquiat memorized after childhood hospitalization. The crossed-out phrases and “missing” inscriptions read like acts of redaction—Black speech disallowed, then resurrected through paint.

Historically, Untitled premiered at the Fast show (Alexander F. Milliken Gallery, 1982) before vanishing into private collections. Its reappearance decades later culminated in a 2017 Sotheby’s sale at $110.5 million, overtaking Warhol and marking Basquiat not as an outsider, but as the late-century master whose syntax rewrote American art.

Technically, conservation analyses—including X-ray and infrared comparisons published in Hoffman’s 2017 catalog and baseline studies from the Brooklyn Museum’s Basquiat conservation program—confirm that the painting was built in “radiographic” layers. Underlayers reveal ghostly marks: half-erased racial epithets, abandoned text clusters, and aborted anatomical sketches. These were not corrections but strategic palimpsests—Basquiat’s method of exposing the interior body and the interior psyche at the same time.

Dealers noted that Basquiat often hesitated to declare such works finished; Untitled (1982) appears to frighten itself into existence, an image that stares back at its creator with the violence of autobiography.

The painting is not only a landmark of Neo-Expressionism and Black avant-garde modernity—it is a visual coroner’s report on America, written by someone whose life was both proof and warning.

updating... shortly

bottom of page